SEINE, Paris, France |

||

|

||

Parc Rives de Seine as seen from the Pont au Change (The Exchange Bridge), with a concrete segment for walking and biking and a grassy area to sit. |

||

In the third century BCE, a tribe of Celtic fishermen known as the Parisii settled on a tiny island, the Île de la Cité, in the midst of my current; this is how Paris got its name. My steadfast body defines the city of Paris and provides an essential point of reference, because I divide the capital into the Right Bank (Rive Droite) on my north side and the Left Bank (Rive Gauche) on the south. When you face downstream the left bank is on your left and the right bank will be on your right. This simple system was devised because my curvy nature often makes orientation difficult. Once a noisy, congested expressway for cars, both of my shores have been transformed into the Parc Rives de Seine (Park Banks of the Seine), a nature-focused pedestrian promenade with play areas for children, open air locavore food outlets, bicycle tracks, and comfortable green spaces to hang out that swaps tarmac for trees and grass. Both banks are listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. |

||

|

|

|||

A street musician with the Conciergerie, a medieval royal palace across the river, and the Eiffel Tower in the far background. |

Notre Dame at night, with people mingling on the left and right banks. |

|||

Distances are measured from my banks and determine street numbers. One might even say that I am the very heart of Paris, with ten of the twenty arrondisements (administrative subdivisions) bordering my shores. Many of the grand monuments are found near me, including the iconic iron architecture of la tour Eiffel; the Grand Palais; the enormous Louvre, with its I. M. Pei-designed glass pyramid; Musée d’Orsay; Musée de l’Orangerie, which houses Monet’s room-sized paintings of water lilies; and the grand Notre Dame Cathedral, especially beautiful when lit at night.

I am 483 miles long (777-kilometers) and a famous waterway, where my backbone is busy each day with traffic from commercial barges and the enormous Bâteaux-Mouches (pleasure boats) carrying tourists to view the city sites. |

||

|

||

Pont de Solferino pedestrian bridge, looking toward Musée d'Orsay. |

||

There is an artist who has actually diverted my flow away from the mainstem, creating a living work of art. Between March 30-August 31, 2018, French artist Stéphane Thidet gave me the opportunity to leave my prescribed riverbed and view the inside of the gothic architecture of the Conciergerie by pumping my water up into pipes that cross the road and into the ancient building, thereby transforming the interior space into a living water installation. The work is entitled Détournement, which means “diversion.” It honors the flood of 1910, caused by impermeable frozen ground and torrential rains that inundated most of Paris causing extensive damage. This national historical monument was used during the French Revolution as a detention center, with its most famous prisoner being Queen Marie Antoinette. Within the Conciergerie there is a high-water mark that delineates the level of the flood within the building. The art installation allows water to enter the Conciergerie, drop over a waterfall, flow through a series of wooden troughs that meander amongst the columns, and eventually exit outside the building in another waterfall, which returns me to my natural channel of the Seine. |

||

|

|

|||

Artist's sketch of water from the Seine being diverted. |

Extracting water from the river and piping it into the Conciergerie. |

|||

|

||

Indoor waterfall. |

||

|

|

|||

High water mark denoting the 1910 flood level inside the Conciergerie. |

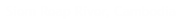

Outdoor waterfall, where water is returned to the Seine. |

|||

From the sublime to the profane, we move from art to shit. Literally, I help transport sewage in a vast city-below-the-city. Visitors can even visit Le Musée des Égouts de Paris, or the Paris Sewers Museum, to learn how the underground tunnels function, while at the same moment, people are sitting on street level at an outdoor bistro with no thought of where their waste will go after they have sipped their cappuccinos and eaten their croissants. The museum opened in 1867, as a way for the public to observe the expensive work that was being done to solve the capital’s wastewater treatment problems! On view are large conduits, cleaning equipment, an automatic flush tank, a storm overflow, and grit chambers. It’s a good idea to bring some nose plugs to help block out the intense odors, since raw, untreated sewage flows right through the museum. |

||

|

||

Stuffed rats on display at the Sewer Museum. |

||

|

|

|||

Equipment inside the Sewer Museum. |

Untreated sewage flowing through the museum. |

|||

For centuries, wastewater was dumped directly into the streets, which unfortunately ended up in my bowels. As Paris grew in population, the situation became intolerable. Rats spread horrible epidemic plagues. In fact, rats are still a common problem today. In January 2018, as my banks began to swell and overflow yet again, the proliferating vermin could be seen in all the arrondissements along my shores. Rife with parasites, these rodents are often immune to poison, and seem to outsmart the city government’s million euro attempts at control measures.

Extensive flooding in Paris occurred in 1910, 1924, 1955, 1982, 1999-2000, June 2016, and January 2018. Hundreds of thousands of works of art from such museums as the Louvre had to be moved out of the city at various times, since much of the art is kept in underground storage units that would be been inundated. I suffer too during these times when my waters rise, because untreated sewage is discharged into me resulting in an oxygen deficit caused by bacteria. The 2018 flood was caused by heavy rainfall, which the Deputy Mayor of Paris, Colombe Brossel, blamed on climate change. He said, “We have to understand that climatic change is not a word, it’s a reality.”

Another unpleasant aspect of being flowing water is that human bodies and human remains are dumped right smack into my guts. In 1431, after Joan of Arc was burned at the stake, her ashes were thrown into my current, washed away, but hardly forgotten. Following the French Revolution, hundreds of victims’ bodies were dredged from my depths. I also provide a popular place for the disposal of murder victims and suicides. Police have discovered floating suitcases bobbing on my surface, containing severed human body parts.

Before pumps were installed, water carriers were paid to haul water from me to private homes. In 1600 there were five thousand carriers, and by 1789, over twenty thousand were lugging buckets back and forth to houses. Henri IV of France had the first hydraulic pump installed in the early 1600’s. It was driven by my current.

In 1832, a cholera epidemic decimated the population of Paris, killing eighteen to twenty thousand people. At this time, no one understood what caused cholera. Some thought it was due to impure air, known as “miasma.” It was not until 1854 that an Englishman, John Snow, discovered that the source of an outbreak in London was due to fecal-contaminated water. This water-borne disease became an important factor in urban planning when it became necessary to institute a series of major sewer works to help eradicate the repeated epidemics, and to solve the twin problems of drinking water and waste disposal. Broader streets were designed that included sidewalks. Gutters that once ran down the middle of the road were placed at the side of the street. Both Paris and London owe their wide boulevards and wastewater treatment plants to an epidemic of a dreaded and deadly disease that I unwittingly helped to facilitate since people would dump raw sewage directly into me without understanding the devastating consequences.

Fortunately, as humans have devised smarter ways to purify drinking water, treat effluent, and facilitate their transportation, I have benefitted too. Today, my park-like banks offer refuge in the heart of a bustling city, and my water is acknowledged as an asset. |

||

next page: San Lorenzo River >

< previous page: Singapore River